Urban organic architecture as a concept is not new, but we need to utilize modern ways to revive it in our 21-century architecture and design.

Organic shapes, inspired by nature, are the most soothing shapes existing. The foundation of organic architecture is rooted in the waking time of human civilization. The history of architecture is the fruit of instincts, just like the beehives or ant habitats. Cappadocia is an excellent example of an organically grown settlement based on intuition, without any centralized planning. We still admire the monuments to progressive design exploration in the legacies of Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto, Antoni Gaudi, or Friedensreich Hundertwasser.

Yet we keep building our shelters in a rigid, restrictive manner believing it’s the most economical and spacious way possible.

Organic Architecture as a Way to Reconnect

To revive organic architecture in our homes, we need designs with natural features within the structure, or/and shaped in harmony with landscaping. Until recently, such buildings required larger lot sizes, which proved as a somewhat limiting factor in individual housing.

What urban organic architecture differs from other forms of organic architecture is the possibility to implement natural shapes and elements within smaller civil lots. A building can be an eco-friendly, sustainable structure with a psychologically harmonizing ambiance without wasting the space or compromising the economic aspect. Bringing natural elements into the living area or incorporating them into the building’s core is the first step.

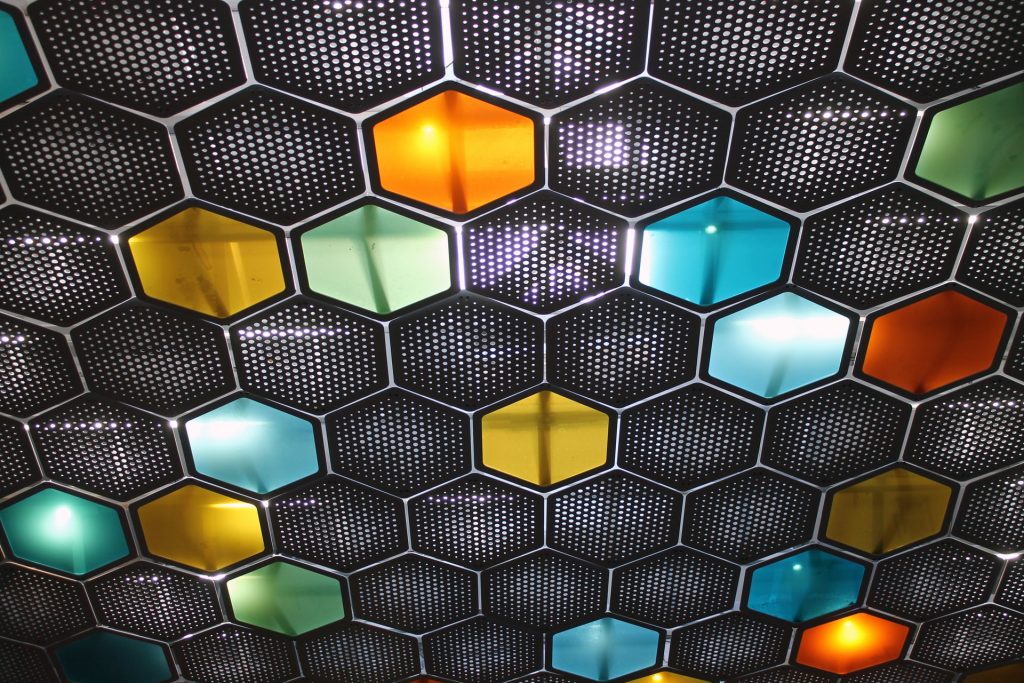

For example, green roofs communicate harmony with nature while also helping with sustainability. Chinese Feng Shui incorporates plants and water as a necessary element in their spiritual philosophy of architecture. Japanese gardens also bring natural elements to the door front to get inspired and soothe the soul. Finally, hexagonal shapes can make an ideal base in achieving zero-net levels of insulation, and a possible future of the passive houses concept.

But still, we live in cubes. Urban living implies a set of lines and forms bent in a perfect 90 degrees angle, manufactured to function as a house, office, or any place we live and work in. We call it “urban jungle” while it more resembles an industrial line.

Why?

Rectangles and cubes are perceived as the most cost-effective shape to build. It’s a practical solution that minimizes the waste of space.

But is that true?

From one point of view, if such a claim is right, then bees are all wrong. But if these hard workers, the epitome of efficiency, are right, then perhaps we need to revisit the whole concept of urban living we know today.

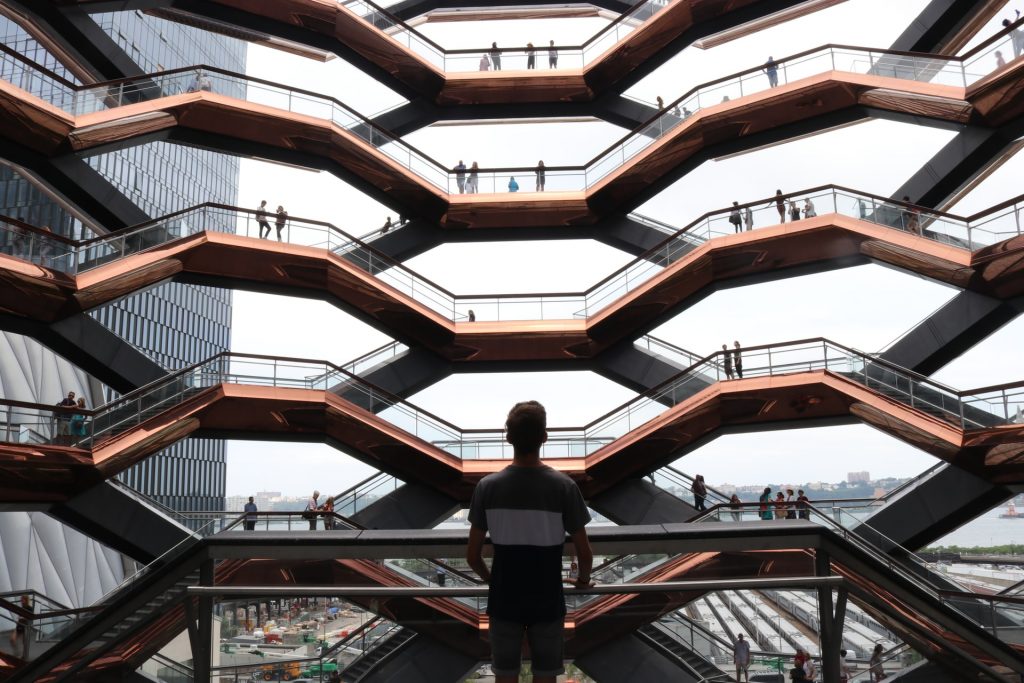

The honeycombs are marvels of precision engineering, an assemblage of prism-shaped cells in a hexagonal cross-section. The wax walls are made with accurate, adequate dimensions, with the cells gently tilted to prevent the honey from running out. Moreover, the entire comb aligns with the Earth’s magnetic field. Bees do not use any blueprint but still somehow manage to achieve geometry, symmetry, and create an efficient space. Nature is wrong much less often than we are, yet we still do not learn enough from it.

Organic Architecture is Intuitive

Bees are able to build perfect honeycombs based on evolved and inherited instincts. Simple as that. If you want to pack together identical cells so that they can fill a flat plane, only three regular shapes will work: equilateral triangles, squares, and hexagons. Now, here is one interesting thing: hexagons require the least total length of the wall, compared with triangles or squares. If bees choose hexagons to save the energy for making wax, does that mean that urban construction could be more cost-efficient based on the same principle?

The answer dates back to the 18th century. Charles Darwin declared that the hexagonal honeycomb is absolute perfection in economizing both labor and material.

The hexagonal grid’s efficiency demonstrates in each line being as short as possible to fill a large area with the fewest number of units. That means the honeycombs require less wax to construct while utilizing strength under compression. Simultaneously, it is one of the only shapes that tessellate perfectly, providing additional insulation benefits.

Not Just the Bees

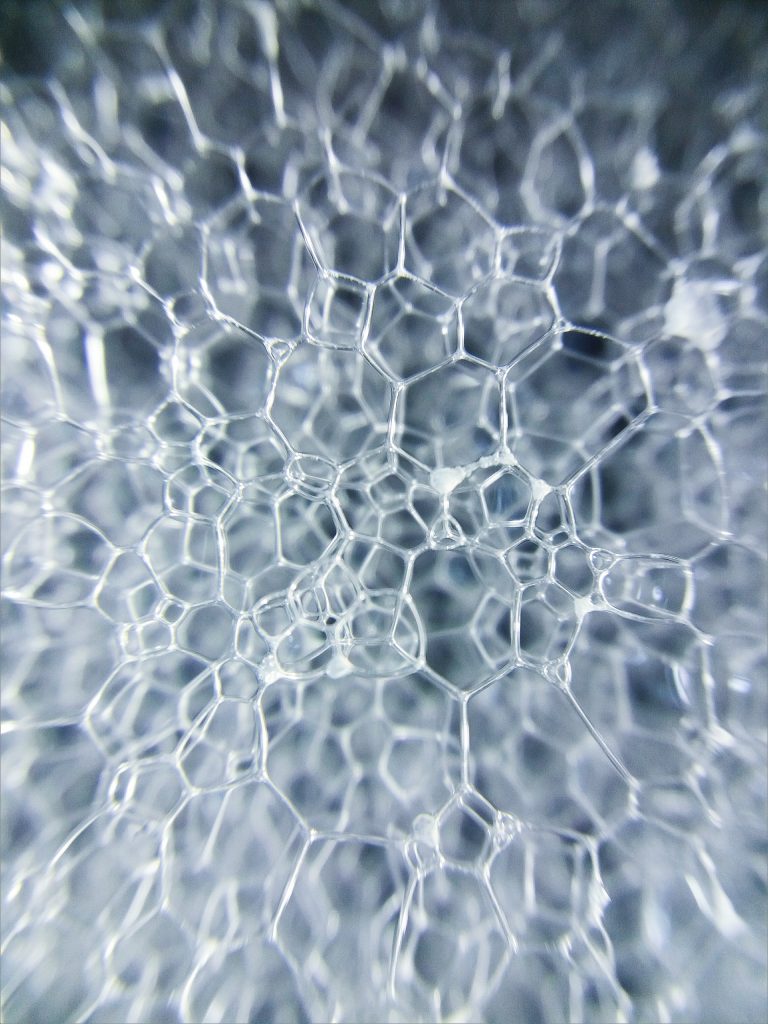

Hexagonal shapes are everywhere in nature. Blowing some air to the surface of the water creates a layer of bubbles. While the bubbles may appear spherical to the eye, they are more of a hexagonal shape—not always perfect 6-siders, but never square. Now, if four bubble walls come together, they rearrange into three-wall junctions. All of those are threefold, intersecting at angles of about 120 degrees.

Blowing air through a straw into a bowl of soapy water will pile up bubbles in three dimensions, creating a four-way union. The angles between the intersection planes closest resemble a tetrahedron. Very efficient, but still no squares.

A single thing guiding all those patterns are the laws of physics. Nature knows its economy, being developing it far longer than humans. A water bubble’s surface tension stretches the wall to cover as much area as possible while remaining mechanically stable and in a perfect balance.

Look closely at a cluster of bubbles in a foam, and you’ll see that their edges are always curved. The pressure of the gas inside the cell changes, and the cells adapt accordingly. Some facets have three sides, some six, yet together they still acquire the tetrahedral arrangement needed for mechanical stability. This tells us that flexibility in shapes doesn’t necessarily imply disorder and loss of function—quite the contrary.

The Water Cube Project

The superior creative intelligence of nature is embodied, among others, in the Water Cube, the swimming stadium built for the Olympic Games in Beijing 2008. Yes, it appears square; however, this highly sustainable structure features several cutting-edge moments. It’s clad with translucent ETFE (ethyl tetra fluoro ethylene), a sturdy, recyclable, and ultra-lightweight material. ETFE weighs just one percent of a standard glass panel in a comparable size. The bubble cladding streams more light than glass. It acts better as an insulator, more resistant to the weathering effects of sunlight. Furthermore, it cleans itself with every rain shower.

Despite the lightweight, fragile appearance, this structural form is durable, extremely sturdy, and resistant to seismic conditions found in Beijing.

The Water Cube is also a greenhouse. Its design allows high levels of natural daylight so that the sun’s power can passively heat the building and water in the pools. This sustainable concept reduced energy consumption by up to 30 percent. In short, the structure acts like it’s covered with photovoltaic panels, equally effective but far more beautiful.

The Water Cube shows us how a sheet can be full of curvature without being obvious. It’s a great way to translate the traditional urban design into a smarter, more sustainable era. A minimally curved surface can turn an ordinary space into an orderly network of passageways known as periodic minimal surfaces. Just like a honeycomb or soap foam, the periodical pattern of cells repeats identically. Think of it as an upgraded train of square apartments or offices, the same model but with far more benefits.

Lessons from Nature

Just like in a foam cluster, the surface tension is stretching the foam film across a wire loop. Where the wireframe is bent, the film also bends, forming an elegant contour. This lightweight concept exists literally everywhere in nature: wings of insects, eyes, fragile exoskeletons… It’s a way to cover any space enclosed by the frame and solve the complicated structuring using the least amount of material. These minimalistic designs bear a lot of potential in terms of sustainability, beauty, and effectiveness.

Tension force is what pull stretches an object to try to make it bigger or longer. Strength marks the ability of a material to resist breaking under such a force. In terms of mass to strength ratio, combining modern technologies with established organic forms is the right path to substantial architectural design improvements. Eventually, that leads us to a better overall quality of life.

To make functional, organized networks from stiff minerals, nature makes a mold. It takes soft, flexible membranes and then crystallizes the hard material inside one of the concentrated networks. Depending on the composition, such elements can strongly bounce off the light, acting like mirrors which guide and confine. Resembling natural optical fibers, architectural structures designed on the same principles can raise energy efficiency to new levels. At the same time, it’s possible to achieve astonishing appearance effects with color changes and optical illusions.

Wright’s Principles of Organic Architecture

Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture was a reinterpretation of nature’s principles. It marks a design filtered through humans’ intelligent minds to remember that they can build forms more natural than nature itself. Over a century, it reminds us to respect the harmonious relationship between the form and the function, integrating the indoor and outdoor spaces into a coherent whole.

Wright’s organic architecture principles bring harmony between shelter and nature, drawing inspiration from the natural surroundings instead of opposing or imitation. Its goal should be to secure peacefulness through simplicity.

Patterns and forms present the grammar in Wright’s building’s language. This concept gives the building its unique voice. Ornamentation also serves to follow the function as a logical part of the structure, seamlessly integrated with its form.

Furniture, light fixtures, appliances, furnaces, and plumbing should be considered part of the space itself, literally growing from the design itself wherever possible.

Urban, Organic and Human

Organic architecture is as old as civilization itself. It represents the true marriage between nature and technology, a harmony between progress and humanism. Organic architecture is a philosophy that asks questions about life itself, offering inspiration. It champions well-being, by addressing the unique needs of the individuals and society as a whole, over a soulless, uniform machinarium.

Instead of austere functionalism, we need to employ a diversity of materials, shapes, styles, and visions. Our goal should be in harmony with nature, complementing it as much as possible. It’s the idea of idealistic urban planning ideology that can lead to a happier, healthier society, inspired by beauty and well-being.

By Aryo Falakrou (My Home Designer)